Point of view: LULUCF – nightmare for sustainable forestry

The forest states in the European Union are finding it increasingly difficult to grasp why the EU is setting out to impoverish the forest-based livelihoods in its member states, and only because of a lack of expertise or even unwillingness to understand. Petri Sarvamaa, a Finnish Member of the European Parliament (EPP) says this political battle “has been simply a nightmare”.

The EU Parliament is to decide next week on how to calculate the size of carbon sinks in the forests within the EU climate policy. Not only are the proposals concerning the LULUCF policy (land use, land use change and forests) beyond reasonable in the case of Finland, but they are also based on a practically complete non-understanding of boreal forestry.

Finnish forests have been a colossal carbon sink for long. They sequester more than half of Finland’s fossil carbon emissions. The thing that Finns have found most difficult to understand is that, according to the least favourable carbon balance calculations, they would not be able to use any of this sink to their benefit.

Other, less drastic calculations would require keeping the sink on its current level. This would mean that Finland could not increase the use of its forests from the present level. On the other hand, increasing the use of forests is an essential part of the bioeconomy policy which Finland has opted for in the interests of a better climate policy.

Forest products could replace fossil ones

What would be the result if the use of forests could not be increased? A great deal of projects are under way in Finland to create new forest-based products. Almost all of them are significantly more climate-friendly than their competitors.

Banning an increase of loggings would pose a direct threat to this development work: plastic bags could not be replaced with new paper bags with substantially improved properties, current textile manufacturing technologies and raw materials, whose impact on the climate, the environment and food production is extremely harmful, could not be replaced with textiles made directly from wood fibre.

A move in this direction would erode the industries’ ability to finance product development and research. We might never see wood-based medications for men’s prostate problems, or several other pharmaceuticals or health products currently being developed.

What is more, we would also have to give up our goals of creating a carbon sink larger than ever in our forests, and this at a moment when we most need it, that is, during the latter half of this century. We would just see another EU paradox: decisions made with good intentions ultimately turn against themselves.

“We can’t afford extra costs”

Last Monday, Finnish climate negotiators received an angry message from the Finnish forest owners – who make up one fifth of the country’s population: a meeting organized by the Finnish landowners’ union MTK made it clear that they would have no business coming back from Brussels with plans involving any extra expenditure for Finns. Speaking at the meeting, MEP Petri Sarvamaa said that the Commission’s plans are just the kind of decisions that make citizens turn against the EU.

The crucial difference in opinions concerning forest use and carbon sinks has to do with the time frame: should we only plan for the period between now and 2050, or should we also take into account the rest of this century, which is what Finland does and which, incidentally, is also in line with the Paris climate agreement, which says that the global carbon balance should reach an equilibrium within the last half of this century.

This requires not only a decrease of carbon emissions, but also the creation of new and effective sinks, as was pointed out on Tuesday by Matti Kahra, specialist at the Finnish think-tank Sitra, at a seminar organized by the Natural Resources Institute Finland (NRI). “We obviously cannot stop all emissions. Since our goal is not only carbon neutrality but negativity, we must be able to remove carbon from the atmosphere,” said Kahra.

For the time being, the most effective tool for this is to grow plants. And, if the plants have economic value, as is the case with trees, creating a carbon sink could well pay for itself.

However, the EU has chosen to extend its climate policy only up to 2044, or 2050. This is also the end point adopted by the environmental organizations, many environmental authorities and researchers.

Finland, however, would prefer to increase its forest use to create a carbon sink that is on a completely new level. Precisely as required by the Paris agreement: in the last half of the century.

This policy may lead to a temporary decrease in the forest carbon sink before 2050, though not necessarily so, because the estimates of forest growth underrate the growth and completely overlook the effect of global warming on forest growth, for example.

We know from preceding years that almost 40 percent of the increase in growth is due to this, as was said in the seminars on Tuesday by Aleksi Lehtonen, research scientist at the NRI.

“After us, the flood”

However, if Finland is able to increase its forest use as planned, the carbon sink in the forests will begin to grow after 2050 by much more than if forest use is not increased. “The reason is that the increase in use would change the age structure of forests,” said Taneli Kolström, Director of Research at the NRI, at the meeting on Monday.

You cannot, however, create a larger sink by keeping forest use on its current level and then starting to work around 2050 – it will be too late. By then the structure of the forests will have changed.

“Explaining this to the EU decision-makers has been most difficult. They do not understand this, but what makes it a nightmare is that many of them do not even want to understand,” said Sarvamaa.

On the other hand, Finnish environmental organizations obviously understand this very well. They are observing a complete silence regarding the years after 2050.

At the meeting organized by MTK on Monday, for example, Jussi Nikula from WWF Finland said nothing about the last half of this century, despite being asked about it more than once.

“After us, the flood.”

In the Commission’s proposal the forest use of the member states would be based on one or several previous years. This would always be detrimental to some member states and advantageous to some others, regardless of which years would be chosen.

Finland, together with some other member states, has proposed that each state could harvest the same percentage of the future growth. In this case, the approved carbon sink would be based on reality, would be simple to calculate and treat all member states equally, and would encourage all countries to increase their forest growth. The idea has gained some support.

If even Iceland is reforesting, why won’t the EU?

Kimmo Tiilikainen, Finnish Minister of the Environment, noted at the MTK meeting that many see forests as passive, unchanging carbon storages. In reality, however, they are dynamic ecosystems. Despite harvesting operations, under sustainable forestry the number of trees and the amount of their biomass is large and increasing.

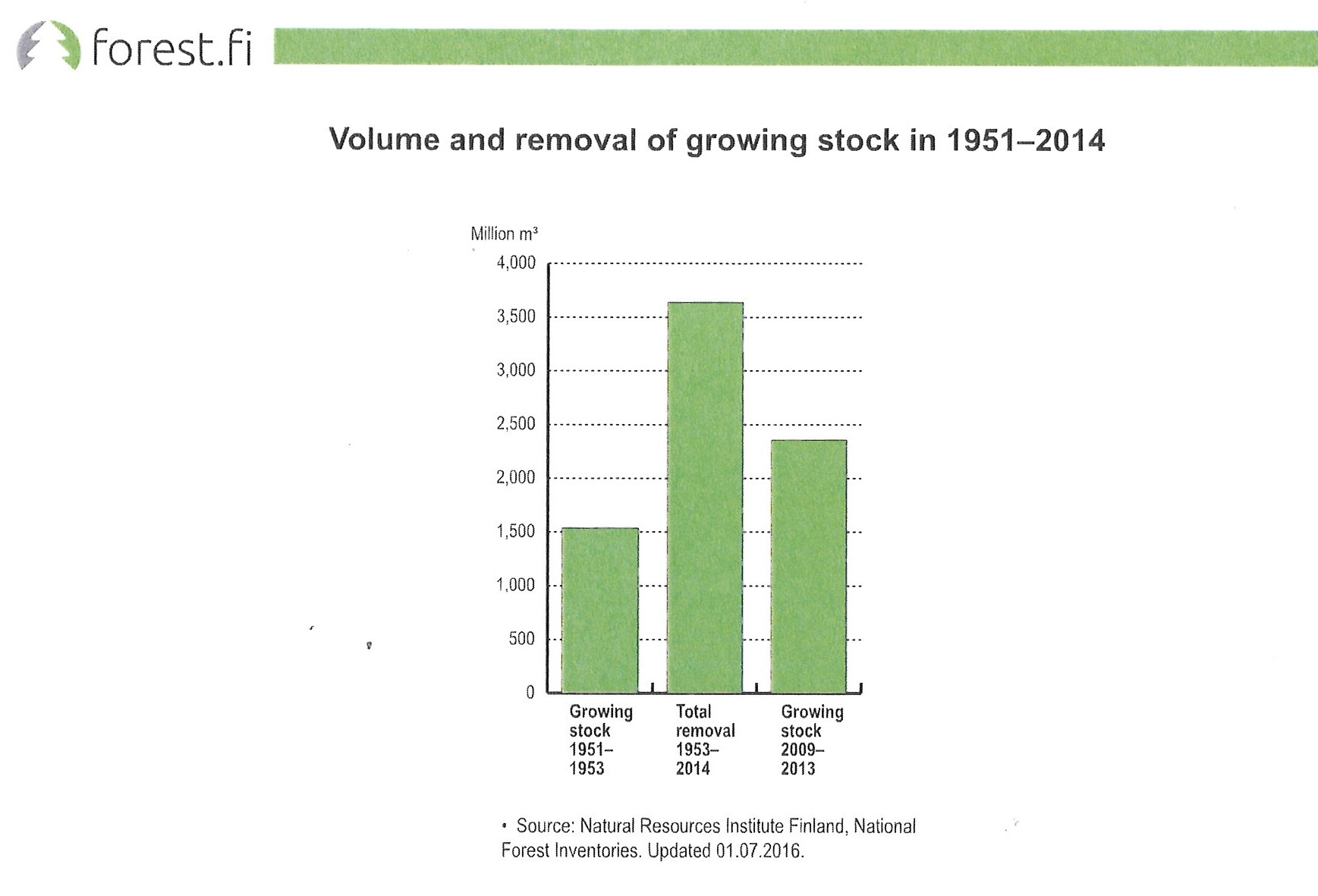

In the case of Finland the timber stock is larger that ever since 1800, which is the time, which the first forest stock estimates concern. And, because the largest increase has been seen since 1950, you can conclude that it is due to the current type of forest use.

Creating similar forest carbon sinks would be possible everywhere in Europe. Instead of making life difficult for those who have maintained their forests, the EU should encourage countries which have destroyed their forests to engage in reforestation efforts.

To give an example: Iceland, some time ago a country completely devoid of trees, has recently created new forests to the extent that they even have a forest industry by now. If this is possible in Iceland, why not elsewhere in Europe?

What is more, this is a rapid method. If work is started now, we will have an enormous carbon sink in Europe after 2050. The sink would also pay back everything invested in it, for the demand for renewable wood biomass is increasing daily.

The potential offered by forest use is enormous. Even now, without any special efforts, the climate effect of the forest carbon sink equals the combined measures taken by the EU to increase the use of wind energy, solar energy and biobased liquid fuels.

The world’s forest area has decreased after prehistoric times, due to human activity, from six to four thousand million hectares. By reforesting the lost hectares and managing them sustainably we could bring the forest carbon storage up to an unprecedented level.

And this would be sustainable also because it would give a livelihood for a great number of

people.

To Harvest or to Save – Forests and Climate Change

Kirjoita kommentti